Tobacco farms, curious formations called mogotes and a tranquil, timeless way of life were what I sought in the tiny colonial city of Viñales in Pinar del Rio – another stop along the Polo Montañez trail, being a favorite haunt of the beloved singer. I found all of that – and a lively nightlife, besides. Maybe a little too lively. Polo’s spirit lingers on, it seems.

Rolling into town I was guided to the bus station, where I coincidentally found the owner of my casa particular – Elio Sanchez, the watchmaker. He hopped on a bike and gestured for me to follow, and soon I was on my way to his charming home just a few blocks from the plaza. He prepared me one of the ubiquitous ham and cheese sandwiches as his wife showed me around. I had my own bedroom, my own bathroom, and my own side entrance to the patio and my room.

I decided to take a guided tour in the afternoon, departing from the city museum and heading off to a tobacco farm, a campesino’s home for a demonstration and a walk around a mogote. We took off on foot down a red-dirt road, past small clapboard homes and into the countryside: Paul, a tourist from London, and our guide, Jesús.

Jesús set out to be the best guide ever. He didn’t know all the answers but he was determined to get them; I made the mistake of inquiring as to the name of a tree with a bright red bloom, and as he wasn’t sure, he asked every neighbor along the way. “If I told you, I’d be a liar,” was a common refrain, producing gales of laughter all around. Finally we established a consensus: the tree seemed to be a piñon, at least according to the neighbors who claimed to know.

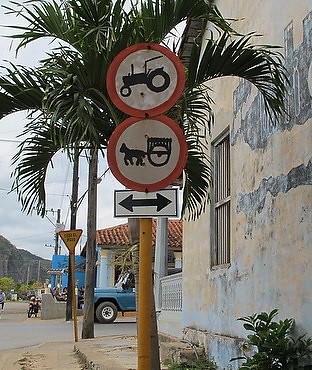

Along the way we passed every sort of transport imaginable; ancient 1950s-era tractors, motor scooters, rickety bicycles, horse-drawn carts, including one driven by a youngster in another world, apparently listening to an MP3 player in one of the oddest anachronisms I’ve seen. My favorite was the bueyes, or oxen. As Jesús and others have explained, during Cuba’s “special period” after the Soviets pulled out of Cuba, petroleum was virtually nonexistent, and the country was forced to return to ox-drawn plows in place of petroleum-powered tractors.

Modern-day industrial farmers didn’t have a clue and had to turn to their rural counterparts for help – like those here in Viñales, who never stopped using oxen. The advantages became evident; oxen didn’t break down and require new parts; they reproduced; they subsisted on grass; and, best of all, they didn’t compact the soil like the tractors did. Instead, their sturdy legs churned through the mud and aerated the soil. They were able to plow when the ground was still far too wet for tractors. And they were able to go places that tractors could never venture.

Paul and I were treated to an unexpected hands-on demonstration of the powers of oxen. Jesús saw a friend with a cart headed down the red dirt road we were walking and hitched us a ride. We clambered on back and bumped along delightedly until Jesús warned us that we were coming to a place where a lake crossed the road. I looked out ahead and the road was dropping away rapidly before our eyes. Suddenly, what looked to be at least a small pond loomed into view. Our oxcart driver continued, undeterred, and the oxen churned their way through a waterway deep enough to sink a tractor. We were truly impressed.

Our tour included a tobacco barn, with the fragrant leaves hanging in bunches, and an explanation of how each leaf is classified and sorted, dried and aged; a tobacco field, where we saw the tender plants with their delicate pink blooms; a visit with a guajiro family, Clara and Gerardo, a mother and son who catered to our vices with home-grown, home-brewed coffee and hand-rolled cigars (I declined on the latter, but Paul declared it excellent, and the coffee was divine).

I reflected on the irony of such an innocent-looking plant claiming so many lives. Gerardo clarified the source of the problem.

“Here in the campo we just smoke our own, hand-grown and hand-rolled cigars,” he said. “There are no chemicals, and we don’t inhale. Nobody gets cancer.”

Finally we got to walk back to a row of mogotes, the strange, Dr. Seuss-looking rock formations that tower over the valley. Some of these formations are home to endemic species that grow only on one or two mogotes, Jesús told us. We clambered up the side of a small one and witnessed a wild array of plant life: cacti, orchids, ferns, agave, and countless unidentifiable species.

We made our way back in time for a sumptuous meal of tender pork meat, black beans and rice and plantains, fruit salad and mojitos at my casa particular – the family had agreed to prepare an extra meal for Paul – and then we headed out to the Polo Montañez Cultural Center, the plaza at the heart of town where the late singer often played.

The seats near the stage were almost taken, but a group of young men happily invited us to join them. Soon Yosniel, a fresh-faced young man the age of my daughter, adopted me as his chosen dance partner. He was a fine dancer – it’s in their blood, he explained – and we danced the night away. I observed Paul receiving a salsa lesson from one of the comely dancers who had been onstage earlier. Good for him, I thought.

It wasn’t until many hours later that we discovered that Paul’s friend didn’t have a place to stay that night. She lived an hour away in another town. “So… how is it that you didn’t realize this before?” asked a perplexed Paul, who had been trying to explain to the woman for some time that he really, truly wasn’t interested. Finally he succumbed to her pleas and agreed to let her stay in his room – but their plans were foiled when the guard asked for her ID. She had none. Under Cuban law, anyone who stays in a hotel must have a state-issued ID.

We took her to the gas station, the only business still open at this hour, where she said she’d find a friend who was keeping her ID for her. This is where my suspicions were confirmed. The man who greeted her didn’t give her an ID, but rather scolded her and sent us on our way. She was apparently a jinetera, the women the guidebooks warn you about, who make their living from attaching themselves in this way to tourists – only this time, it didn’t work.

We took Paul back to his hotel, and now it was my turn. Yosniel, it seems, lived four kilometers away on a cowpath in the woods, and unless I could drive an ox, I couldn’t take him home. I’m a sucker for sad eyes, and I let him stay in my room. Only the next morning after he had slipped out early did I realize, when the owner of my casa particular confronted me, that locals are not allowed into the casas particulares.

“I could lose my business over this, if an inspector stopped by,” she scolded. “He should have known better.”

I apologized profusely and hung my head like a child. Oh, well, I sighed. Polo Montañez’ party-loving spirit seemed to chuckle nearby. I plugged in his CD and headed off into the morning, through the mist-draped mogotes to the North Coast.

Created with Admarket’s flickrSLiDR.

Leave a Reply