My time in Colombia was so full of amazing people and organizations that it didn’t leave me time to write as much as I would have liked. This roundup gives a little information about each of them, with hopes to come back to each of them with more information later.

Perhaps more than any country in Latin America, Colombia has suffered the pains born of a savagely unequal distribution of wealth and the gross distortions of humanity that can evolve such a system. Colombia is a land of extremes: beginning, as the entire story of Latin America does, with the Spanish conquest – but more recently, with La Violencia, the decade-long wave of violence unleashed by attempts at land reform in the 1940s and ’50s. This brutal backlash laid the groundwork for guerilla, military and paramilitary violence that wracked the country for four decades, laying the groundwork in turn for the narcotrafficking that accelerated the violence, until recently, to the point of paroxysm.

Thankfully, those days are in the past, and Colombia is working hard to show the world another side: an industrious, modern, spectacularly beautiful country that’s ready to charm the world. But there’s another side to this land of magical realism, as well, and this is the side I witnessed in my recent monthlong stay – a side that is fervently dedicated to nonviolent solutions, and to a shift to a more sustainable, more equitable way of life. That month was only long enough to get a sense of the depth and the breadth of these movements for social change, and for the passionate and creative approach of Colombian world-changers and their commitment to the task – just long enough to fall in love with this country, which moved me so much that I wept on the flight north as I watched its green mountains recede into the clouds.

My initial purpose for visiting Colombia, and the reason I began in Cali, was because I was invited by ProExport, a government agency promoting tourism, to do an article on the salsa scene in what has arguably become the World Salsa Capital. My first week was lost in a whirl of salsa lessons, interviews with teachers and experts and performers, visits to salsatecas old and new, and the world-class salsa circus extravaganza, Delirio.

My initial purpose for visiting Colombia, and the reason I began in Cali, was because I was invited by ProExport, a government agency promoting tourism, to do an article on the salsa scene in what has arguably become the World Salsa Capital. My first week was lost in a whirl of salsa lessons, interviews with teachers and experts and performers, visits to salsatecas old and new, and the world-class salsa circus extravaganza, Delirio.

Here I want to mention the work of Mauricio Novoa of Rioja Travel, who is working to bring more visibility to those who deserve it – and need it – the most. His tour shows the rugged underside of the salsa world: the salsatecas in the Barrio Obrero where street vendors and mechanics dance their hearts out along with businesses owners and schoolteachers, and nobody worries whether they’re stylish or proper; to the teachers from the working-class barrios who are working with at-risk youth to keep them off the streets and steered toward a life where they will have a chance at a better future; and the youngsters themselves, many of them grade-schoolers, whose enormous discipline and steadily channeled passion shows in their masterful moves on the dance floor. These schools included Diego Rojas’ Pioneros del Ritmo, Carlos Sánchez’ Sabor Latino and Vivian and Ricardo’s Estilo y Sabor, who participated in the Delirio extravaganza with standout performances. Here are some images from Cali’s salsa scene.

Here I want to mention the work of Mauricio Novoa of Rioja Travel, who is working to bring more visibility to those who deserve it – and need it – the most. His tour shows the rugged underside of the salsa world: the salsatecas in the Barrio Obrero where street vendors and mechanics dance their hearts out along with businesses owners and schoolteachers, and nobody worries whether they’re stylish or proper; to the teachers from the working-class barrios who are working with at-risk youth to keep them off the streets and steered toward a life where they will have a chance at a better future; and the youngsters themselves, many of them grade-schoolers, whose enormous discipline and steadily channeled passion shows in their masterful moves on the dance floor. These schools included Diego Rojas’ Pioneros del Ritmo, Carlos Sánchez’ Sabor Latino and Vivian and Ricardo’s Estilo y Sabor, who participated in the Delirio extravaganza with standout performances. Here are some images from Cali’s salsa scene.

After my salsa week, I met with a number of inspiring people who are approaching environmental preservation and justice from a variety of perspectives.

There was chef Catalina Velez, owner of top-rated restaurants Kiva and Luna Lounge and a star chef featured on the Gourmet Channel throughout Latin America. Catalina is a leader in the organics and local foods movement, working hard to preserve heritage foods and to find markets for local organic and “clean production” farmers. It was Catalina, a loyal volunteer with VallenPaz, who told me about this organization, which was born of the violence when a mass kidnapping in a popular dining spot outside of Cali led its founder to seek the social roots of that violence. VallenPaz works with nearly 9,000 producers in conflict areas in three departments to help them professionalize their operations and to work directly with supermarkets, restaurants and consumers instead of costly middlemen.

There was chef Catalina Velez, owner of top-rated restaurants Kiva and Luna Lounge and a star chef featured on the Gourmet Channel throughout Latin America. Catalina is a leader in the organics and local foods movement, working hard to preserve heritage foods and to find markets for local organic and “clean production” farmers. It was Catalina, a loyal volunteer with VallenPaz, who told me about this organization, which was born of the violence when a mass kidnapping in a popular dining spot outside of Cali led its founder to seek the social roots of that violence. VallenPaz works with nearly 9,000 producers in conflict areas in three departments to help them professionalize their operations and to work directly with supermarkets, restaurants and consumers instead of costly middlemen.

I spent a couple of days with VallenPaz staff, interviewing Executive Director Luis Alberto Villegas, who has helped turn the organization into an economic powerhouse, bringing to market some $19.5 million in products grown and produced by small farmers. What’s more, the organization is promoting sustainable farming or “clean production” techniques, encouraging farmers to make the transition to organic, or at least dramatically reduce chemical inputs through the use of sustainable farming techniques.

I also visited with Isabel Cristina Romero, who told me of working in guerilla-controlled zones to help farmers negotiate with the rebels instead of fleeing their land; Laura Mejilla, who has worked with producers to help them create value-added products like organic preserves and “moneditas” or crunchy plantain snacks. And I took a trip out to the farm of Norberto Mina, a former farmworker who is now a proud empresario of his own farm, thanks to the efforts of VallenPaz and other organizations. He was negotiating with a couple of businessman about investing in a tilapia pond on his land when we left.

I also visited with Isabel Cristina Romero, who told me of working in guerilla-controlled zones to help farmers negotiate with the rebels instead of fleeing their land; Laura Mejilla, who has worked with producers to help them create value-added products like organic preserves and “moneditas” or crunchy plantain snacks. And I took a trip out to the farm of Norberto Mina, a former farmworker who is now a proud empresario of his own farm, thanks to the efforts of VallenPaz and other organizations. He was negotiating with a couple of businessman about investing in a tilapia pond on his land when we left.

Here are some images from my visit to Norberto’s farm in Guachene, department of Cauca.

One of my Cali highlights was birdwatching with Mapalina, an unusual ecotourism group founded by biologist Carlos Mario Wagner and a group of underprivileged youth. Wagner was surveying birds in the highlands near Cali when he met several young people from the poor communities around the area who were intrigued by what he was doing. Jose Luna Solarte was one of them; like most of the kids in these remote areas, he never had access to a good education, and his job prospects didn’t look good. Wagner’s passion for the birds captured Solarte’s attention and he began studying the birds. Now he forms part of a team of highly skilled birding specialists who conduct ecotours and lead international researchers through the cloud forests above Cali.

One of my Cali highlights was birdwatching with Mapalina, an unusual ecotourism group founded by biologist Carlos Mario Wagner and a group of underprivileged youth. Wagner was surveying birds in the highlands near Cali when he met several young people from the poor communities around the area who were intrigued by what he was doing. Jose Luna Solarte was one of them; like most of the kids in these remote areas, he never had access to a good education, and his job prospects didn’t look good. Wagner’s passion for the birds captured Solarte’s attention and he began studying the birds. Now he forms part of a team of highly skilled birding specialists who conduct ecotours and lead international researchers through the cloud forests above Cali.

The Mapalina team took me up to Kilometer 18 and to the San Antonio Cloud Forest, designated an IBA (Important Birding Area) by BirdLife International. The highlight of the visit was a trip to Finca Zingara, home to literally hundreds of hummingbirds, all whom have been hand-fed by Asdrubal Corrales for the past seven years. Here I sat on the balcony and watched as the fairy-like creatures buzzed and zipped from feeder to feeder, one of them finally coming to rest on my finger as I sat very still and held a feeding dish. It was an unforgettable thrill.

The Mapalina team took me up to Kilometer 18 and to the San Antonio Cloud Forest, designated an IBA (Important Birding Area) by BirdLife International. The highlight of the visit was a trip to Finca Zingara, home to literally hundreds of hummingbirds, all whom have been hand-fed by Asdrubal Corrales for the past seven years. Here I sat on the balcony and watched as the fairy-like creatures buzzed and zipped from feeder to feeder, one of them finally coming to rest on my finger as I sat very still and held a feeding dish. It was an unforgettable thrill.

Jenny Farranda Jordan, one of the Mapalina team, explained what motivated her to spend all her free time learning to identify birds and guide tours.

Jenny Farranda Jordan, one of the Mapalina team, explained what motivated her to spend all her free time learning to identify birds and guide tours.

“When someone begins to relate with nature, they begin to develop all their senses; they become more human, in a way,” she said. “Birds are a great vehicle to sensitize people to the wonders of the world around them.”

Here are some images from my morning with Mapalina.

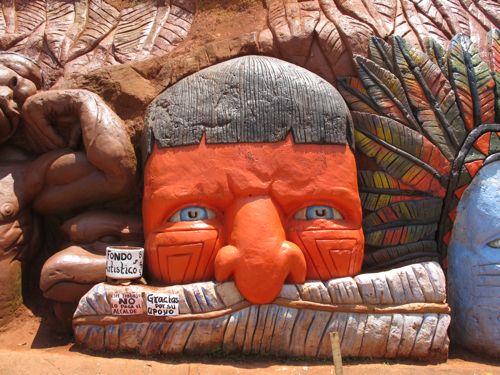

Sculptor Carlos Andrés Gómez, whose medium is nature itself, was another remarkable Caleño who is making his mark on the city with “El Lamento del Pachamama,” an astounding work of art he is carving into a hillside across from a discoteque that was the site of a massacre during the height of the city’s drug violence. Gómez is striving to bring the abandoned area back to life by creating a tourist attraction that depicts the beauty and pain of the Mother Earth and her relationship with her conflictive and often destructive human children.

Sculptor Carlos Andrés Gómez, whose medium is nature itself, was another remarkable Caleño who is making his mark on the city with “El Lamento del Pachamama,” an astounding work of art he is carving into a hillside across from a discoteque that was the site of a massacre during the height of the city’s drug violence. Gómez is striving to bring the abandoned area back to life by creating a tourist attraction that depicts the beauty and pain of the Mother Earth and her relationship with her conflictive and often destructive human children.

Here’s a video interview I did with Carlos that shows the work in progress and explains the story of what happened here.

Perhaps the most fascinating Caleño and the one who made the greatest impact for me was William Salazar, a Colombian shaman and the founder of Verdeverdad Social and Environmental Network and a new healing center, Agua Viva, dedicated to raising awareness through indigenous ceremonies with the use of the sacred medicinal herb known as yagé, or ayahuasca. Salazar, a former seminarian, philosophy professor and political activist, spent 17 years studying indigenous wisdom from the elders of Putumayo in the Colombian Amazon. His studies brought him to the conclusion that only a major shift in human consciousness could save the planet, and that yage can be an important vehicle in that shift.

Perhaps the most fascinating Caleño and the one who made the greatest impact for me was William Salazar, a Colombian shaman and the founder of Verdeverdad Social and Environmental Network and a new healing center, Agua Viva, dedicated to raising awareness through indigenous ceremonies with the use of the sacred medicinal herb known as yagé, or ayahuasca. Salazar, a former seminarian, philosophy professor and political activist, spent 17 years studying indigenous wisdom from the elders of Putumayo in the Colombian Amazon. His studies brought him to the conclusion that only a major shift in human consciousness could save the planet, and that yage can be an important vehicle in that shift.

During my time in Cali, Salazar invited me to a ceremony with two taitas or shamans from the Ecuadorean Amazon, and I accepted. The journey was indeed consciousness-altering, a profound departure from the mundane world and a glimpse into other realms. I will be publishing more information, an interview with Salazar and an account of my experience soon. Meanwhile, here are some images from an unforgettable three days at Agua Viva Healing Center, taken by me and artist/photographer Carlos Ruiz.

No account of my time in Cali would be complete without mentioning El Hatico, the agricultural reserve gaining international recognition for its innovative use of silviculture in cattle ranching. The full story is here.

Medellin was filled with another series of colorful characters and consciousness-raising experiences, but that’s a story for another day. Meanwhile, Cali is calling to me, and it seems to me I left a part of me there. Something tells me I’ll be back there one day soon.

Leave a Reply